Sustainable Finance and the Overlooked Role of Central Banks

When people discuss sustainable finance, the focus is typically on regulators like the European Commission, investors, and companies. However, central banks, despite their significant impact, are often overlooked.

It basically started in 2015. Back then, Mark Carney was not Prime Minister of Canada but Governor of the Bank of England. He gave a speech called “Breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon – climate change and financial stability”.

The speech is still worth reading or watching 10 years on where he roughly outlined three channels how climate change can affect financial stability:

- Physical Risks: Immediate impacts on insurance liabilities and asset values arising from climate- and weather-related events, such as floods and wildfires.

- Liability Risks: Future financial implications if parties suffering climate-related damages seek compensation from polluting firms.

- Transition Risks: Financial risks emerging from policy shifts, technological advancements, and physical risks as economies adjust toward lower-carbon models.

I am not sure about the liability risk for emitters as it seems unlikely that Shell or ExxonMobil will have to pay for damages in the future. However, the first and the third category of risks are very real.

Just consider the costs of the recent wildfires in the neighborhoods of Pacific Palisades and Malibu. The Los Angeles Times reports that the cost estimates of the fire are in the range of $250 billion. The picture below is a good indication of the damage.

In the speech, Mark Carney also outlined the need for better disclosure as an option to address these risks for investors and regulators. Disclosures is one of the key regulatory levers to achieve the goal of redirecting capital flows towards sustainability-related investment targets.

Climate stress testing

In 2022, the European Central Bank conducted a climate stress test. It was the first study of this kind in the Eurozone and aimed to start a process in which banks build their data infrastructure and collect climate-relevant data.

It was noted in the report that “overall, banks have made widespread use of proxy data to compile key data points for Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions and Energy Performance Certificates”. That does not seem like an approving statement. However, it kick-started a development process.

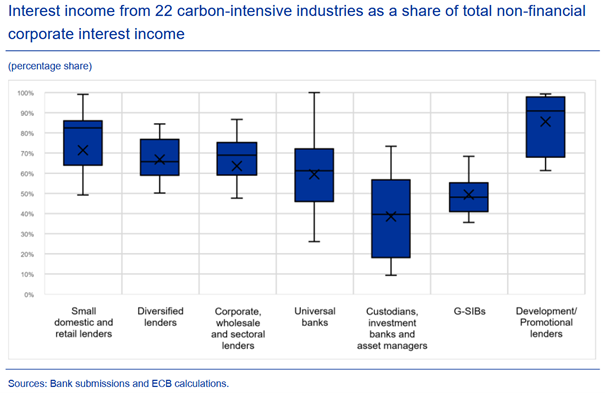

Overall, they find that around 60% of corporate interest income was coming from customers in carbon-intensive sectors. The number should not be taken at face value as most of the interest income is coming from retail and real estate. Real estate is on a downward trend when it comes to carbon emissions as new buildings are more energy efficient and there are public incentives to upgrade the existing housing stock such was in the Renovation Wave which aims to renovate 35 million buildings across the European Union.

The chart below illustrates the „Interest income from 22 carbon-intensive industries as a share of total non-financial corporate interest income.“ The chart shows the percentage share across different types of lenders, including small domestic and retail lenders, diversified lenders, corporate, wholesale and sectoral lenders, universal banks, custodians, investment banks and asset managers, G-SIBs, and Development/Promotional lenders.

Similar findings are echoed by the Bank of England in their study titled “2021 Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario”. It may sound obvious, but carbon-intensive industries and sectors exposed to physical risk are more likely to contributed to future losses. Deutsche Bank Research has found that “Southern European banks have more than 60% of their corporate loans exposed to high physical risk.”

Supervisory work

These results were always meant to support banks improve their risk management systems by integrating climate-changed related aspects and informing the supervisory work.

In 2022, the ECB also outlined what they want to see over the next 48 months:

- By March 2023: Banks were expected to identify and categorize climate and environmental risks, conducting a full assessment of their impact on operations.

- By end-2023: These risks were to be embedded within banks’ governance structures, strategic planning, and risk management practices. Despite early progress by some institutions, many banks continued to adopt a passive stance, often failing to set interim targets or implementing changes that yield negligible short-term impacts.

- By end-2024: Full integration of climate risks into supervisory frameworks including the Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP) and stress-testing is required.

That is an ambitious piece of regulatory work. The thinking is that once you have the data, you start working with them and take decisions which are more closely related to climate-related risks.

Positively, the ECB is also following through on these aspects. In 2024, the ECB issued binding supervision against nine entities which failed to comply with these decisions. These might lead to periodic penalty payments.

Just take a moment to think about it. The ECB conducts stress tests, provides guidance for the largest banks to improve their risk models and fines them if they do not comply.

Green tilts in asset purchases

Two additional aspects of the ECB’s role are noteworthy. The ECB is buying assets as part of its policy toolbox. The quantitative easing has stopped but the ECB still holds trillions of assets across two different programs. The asset purchase programme (APP) has a volume 2,567 billions, while it is still holds 1,524 billion in the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP).

In 2023, the Governing Council of the ECB decided “for the Eurosystem’s corporate bond purchases, the remaining reinvestments will be tilted more strongly towards issuers with a better climate performance.” The ECB is also buying sustainability-linked bonds which is a good market signal.

Just consider the implications. One of the biggest buyer of bonds in the Eurozone is saying that climate performance is playing an important role in the investment decision. That is a very powerful market signal.

Regulatory developments

The ECB is also taking an active role in shaping EU-level regulatory developments. The European Commission has recently published an opinion on the on proposals for amendments to corporate sustainability reporting and due diligence requirements.

The key take-away is that the ECB stresses the importance of these disclosures for the integrity of the financial system. They state that “competent authorities, including the ECB, are required to ensure that credit institutions have robust governance and risk management arrangements to identify, measure, manage and monitor ESG risks over the short, medium and long term, and that credit institutions test their resilience to long-term negative impacts of ESG factors”.

Data quality and coverage is a topic which I have also covered in the book and is frequently covered in the position. For example, the ECB has warned that if fewer companies fall under the scope of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), banks will face significant data gaps in ESG risk assessments.